Author: Tyler Huang

Brunswick High School

September 1, 2021

Abstract

Million of Americans across the country currently live below the poverty line, and this issue has only been exacerbated by the ongoing pandemic. Studies have shown that poverty directly relates to health and wellbeing. This research paper describes the myriad ways lower-income communities struggle to gain access to nutritious foods, and how the stagnation of wages is a major factor of the ever rising poverty rate. I also conducted field-work at a local food shelter to experience first hand the problems of food insecurity and poverty that lie within the local community.

Vignette

Since middle-school, I have volunteered at a local food bank located within walking distance from my family’s Chinese takeout restaurant in Brunswick, Georgia. My experiences as a volunteer have deeply informed my interest in the topic of food scarcity. Moreover, it has provided me with first-hand insights into the challenges of hunger and poverty among low-income households within my community. The following vignette is based on my observations from two different morning shifts in early and mid-July 2021.

Field Notes

It is early July, and I worked my usual volunteer shift from 9 am until 12 pm. I arrived at Nest 5 minutes before opening (at 8:55 am), and I saw a group of 5 people, who were already waiting in line for the food bank to be open.

Today was a rather hot and humid day (around 90!), so I saw many people carry umbrellas to shield themselves from the sun as they waited in line to get registered for food. I also saw some using the registration papers to fan themselves to get a breeze and cool the sweat off their faces. Many of the people waiting in line bore noticeable signs of exhaustion. They closed their eyes and leaned on the graffitied walls when waiting in line.

I asked a few of them, “Hey, how are you doing?”

One person said, “I’m doing okay, just tired.”

Another person replied, “I’m just taking it a day at a time.”

Through my past conversations, I knew that most of the people receiving food live only a few blocks away from the Nest or near downtown. While two people had out-of-state drivers’ licenses like Florida and South Carolina, most people are local residents. The public housing apartments is located just one block away, which makes it convenient to walk over to the food pantry.

During those morning shifts, roughly 25 people received food, with roughly a dozen being women, about ten men, and a handful of elderly (over the age of 65). Of those twenty-something people who receive food, about three fourths typically have children (17 years old and younger) whom they are also getting food for. By looking at the driver’s licenses, almost all of the people lived either near downtown Brunswick or the nearby government housing.

During my shifts, I do a variety of tasks. One task is filling bags that contain Kraft mac-n-cheese, rice/pasta bought in bulk from America’s Second Harvest, donated cans of tomato sauce, Campbell’s chicken noodle soup, and Del Monte corn and green beans. Sometimes food bank volunteers would also add in random snacks that were donated, such as Kind bars, Doritos, and M&M candies. Another task is sorting the new donations–bread and various canned goods and vegetables–and stocking the shelves. I also distributed food. Doing the distribution meant I determined how many people were in the household and then handed out the correct number of bags. That day, I had toiletries in stock, so everybody received a bag containing toilet paper, toothpaste, toothbrushes, and soap. Sometimes when we received shipments of fresh produce, I asked if they wanted fresh produce and nearly everyone accepted this offer of produce (broccoli, squash, carrots, peppers, etc.).

Although we did not have any fresh produce on this day, we received a donation of personal/ family-sized salads, sliced fruits (pineapples, watermelons, and cantaloupes), and bread that were about 2 days away from the expiration date from the grocery store Harris Teeters.

I asked each person “We have salads and fruits today; would you care for some?”

Most replied, “Sure.” or “Yes please.”

I also stocked the shelves and sorted the new donations by expiration year. While distributing the food, I had to look at how many people were in the household and then give out the correct number of bags. There was a person that had 7 children, so I gave them a “Momentum Box,” which is donated by the local church that was made specifically for large families. The Momentum Box contains three family-sized cereal boxes (Honey Nut Cheerios) and canned food that equates to roughly six adult bags that we ordinarily give out. My responsibilities were to ensure that people who came into the food bank were being cared.

Brunswick, Food Scarcity and Poverty

I grew up in the small town of Brunswick, Georgia. Brunswick has a population of around 16,000 people, and poverty is not out of the norm. Poverty experiences are not unusual for people living in rural parts of the state, as Georgia’s poverty rate has exceeded the U.S. poverty rates every year since 1999. According to the Census Bureau, Brunswick is one of the poorest cities in Georgia, and poverty rates in Brunswick have exceeded Georgia’s poverty rate every year since 1999 as well. Brunswick’s median income for a household was $28,032 for 2019. Around 34.7% of the population was below the poverty line, which almost tripled the 13.7% national poverty rate.

These numbers are staggering when just an eight-mile-long car drive to St. Simons, the poverty rate dips 5.2%. According to the Census Bureau, the median household income of Brunswick is $24,417 whereas, in St. Simons, it is $78,782. Furthermore, in 2017, the average net worth of a household in Brunswick was $156,363 compared to $1,744,845 in St. Simons. These statistics go to show the drastic disparities of income and lifestyle choices in the short distance of 15 miles.

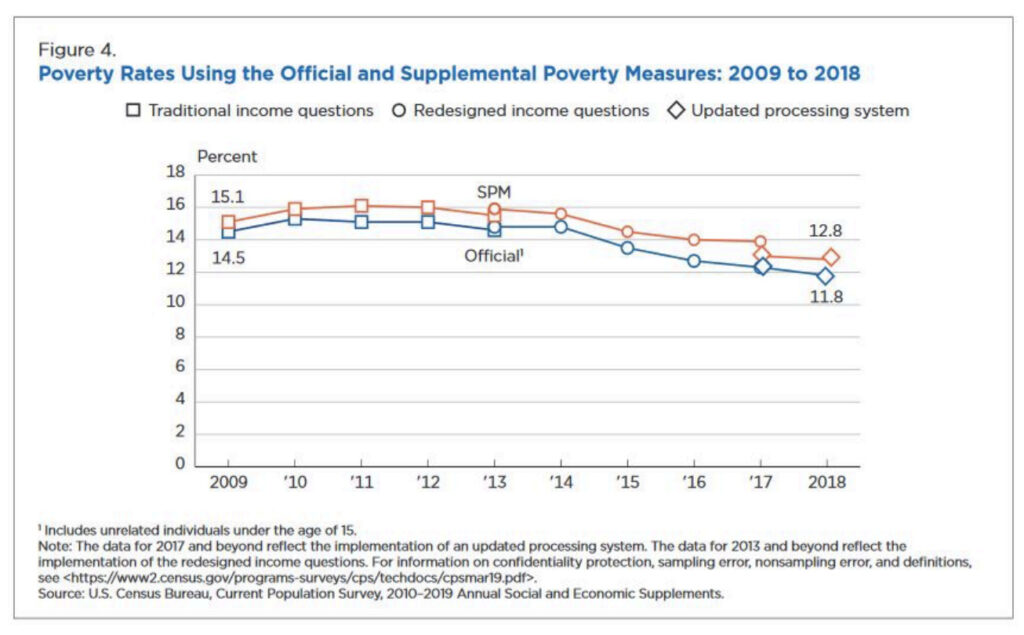

On a national level, the poverty rate in the United States has been trending upwards over the past decade, and this issue has been further deepened by the ongoing pandemic. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the U.S. economy lost 22 million jobs from February to April 2020 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). In January, some 24 million adults reported experiencing hunger (Congressional Research Service). With a disconcerting amount of job loss not seen since the Great Depression, poverty and poor health have taken a toll on many, especially those in lower-income communities.

Poverty has many adverse effects and is directly related to diet and health issues. Depending on one’s socioeconomic status, a person’s health can vastly differ based on their income. This is referred to as the “social gradient in health,” which is used to describe the phenomenon where people who are less advantaged in terms of socioeconomic position have worse health (and shorter lives) than those who are more advantaged (Institute of Health Equity). What this means is that as income goes up, life expectancy and the ability to access higher-quality foods increase as well.

Ultimately, factors such as neighborhoods, costs, and behavior are all affected by poverty. As such, it is imperative to understand the underlying effects of how poverty is detrimental to health and overall well-being and find fruitful solutions to these issues. As Sandro Galea states, “Money purchases better food, better neighborhoods, political influence, and, crucially, peace of mind. If you need help raising your children, money lets you afford daycare. The Urban Institute found that the less money a person has, the less likely he/she is to have paid sick/ vacation leave and pension or retirement contributions; a neighborhood with sidewalks, parks, playgrounds, and a library of report good health.”

How does not having money undermine health? It makes us less likely to have a decent home in a safe neighborhood, to eat high-quality food, to receive a good education, or to live a long life. While it is true that all groups experience some hardship and stress, however, if you need a break from the psychological stress of work, for example, money lets you take a vacation or pay for quality therapy. This mosaic of advantages translates into better health.

Neighborhoods (the environment) in which a person’s life plays a large role in health and diet. In areas with lower incomes, some barriers prevent one from easily accessing healthy foods. According to data from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), roughly 23.5 million people live in food deserts. Food deserts are areas in which people have a hard time acquiring healthy and nutritious foods because they live in areas far away from grocery stores. Nearly half of the people in such circumstances are also low-income.

Over 2.3 million people (2.2% of all US households) live in low-income, rural areas that are over 10 miles from a grocery store (USDA). The most prominent reasons as to why food deserts occur include, but are not limited to, zoning restrictions, high- levels of crime in a certain neighborhood, and other factors like higher operating costs for grocers in low-income areas, which can make businesses hesitant to set up shop there.

Furthermore, another primary factor that contributes to the lack of access to food in rural areas is the lack of transportation. Unlike in urban cities where reliable public transportation is readily available, smaller cities are spread much more apart. In rural cities, the absence of basic public transportation services means that the only way to travel efficiently is by car, which is a problem since many people in food deserts do not have the economic ability to do so. Thus, people who live in food deserts suffer from limited accessibility of fresh and nutritious foods and impedes the ability to have a healthy diet.

Even in the chance that there are nearby small local grocery or convenience stores with fresh produce in stock, prices may be too expensive when compared to supermarket prices. As a result, people that are living in food deserts may turn to more accessible alternatives, such as fast-food restaurants, frozen meals, etc. which are unhealthy. Unfortunately, many struggle to eat anything at all.

The lack of access to healthful foods and easy access to fast foods is linked to poor diets that are high in sugar, sodium, and unhealthful fats. This can contribute to diet-related conditions such as high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and increase the chance of Type 2 diabetes (Smith 2009). Diet quality is strongly correlated to one’s socioeconomic status. For example, wealthier individuals can afford healthier and higher-quality foods, such as whole grains, fish, and lean proteins. Fresh fruits and vegetables are also more likely to be consumed by those with a higher socioeconomic status. On the contrary, as income levels drop, high-calorie and nutrient-poor foods become a staple in diets when trying to meet the daily minimum calorie intake. Cheaper foods such as canned goods are more likely to be energy-dense but also less healthy. The reason is that people with lower incomes prioritize getting the basic physiological needs, as depicted by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Canned foods, microwavable foods, and highly processed foods staples are readily available and cheap but are all loaded with fat and sodium that are way over the daily limits. This leads people with lower socioeconomic status have dietary profiles that often don’t meet the daily requirement, thus contributing to their poorer health. The graph below depicts the various effects poverty can cause.

Poverty → diet & food selection

Poverty → less money

Poverty → less resources (transportation/education/information/time/health

literacy)

Poverty → more stress

These low-cost food options are also lower in nutritional value. In contrast, nutrient-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables are often cost prohibitive for lower-income people. A significant body of evidence shows how healthy foods cost more than unhealthy foods. According to Donkin, “The price of vegetables, for example, costs nearly twice as much when measured as “price per 100 calories” than when it was measured as “price per edible gram” or “price average portion” (roughly $3.75/100 calories vs. $1.60 and $1.40, respectively).” These data go to show that healthier items such as fresh fruits and vegetables on average cost more than their less healthy counterparts. Shown below is a relationship of how cost and diet selection affect health.

Proximity/cost/availability→ diet & food selection

fast/cheap food → less nutrients

fast/cheap food → more fat/cholesterol

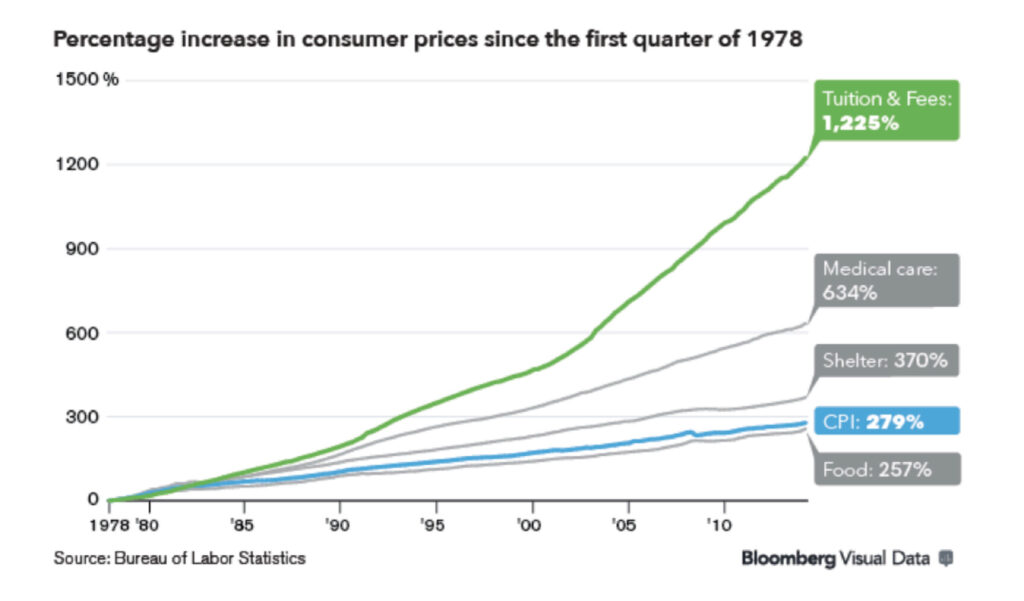

Furthermore, an important aspect that many seemingly overlook is the impact that poverty can have on mental health. One out of five people suffer from some mental disorders, and poverty in adulthood is connected to depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and even suicide (Simon 7). Lower income individuals often suffer more from the harshness of mental illness as opposed to someone with a higher income. The reason is that economic inequality is linked to disproportionate access to help. Lower-income families are often struggling to make ends meet and cannot afford to spend money to seek help or consult a therapist. This, unfortunately, results in people of lower socioeconomic status having a higher likelihood of developing mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. The financial burden is already overwhelming and constant worrying may lead to more problems. Also, the stigma around mental illness is not helping either, as many may feel ashamed to seek help. Another major factor on why poverty is increasing is because costs have gone up. It has become harder for Americans to obtain a comfortable standard of living because housing costs, food costs, and necessities have gone up in price, thus posing a threat to their financial security.

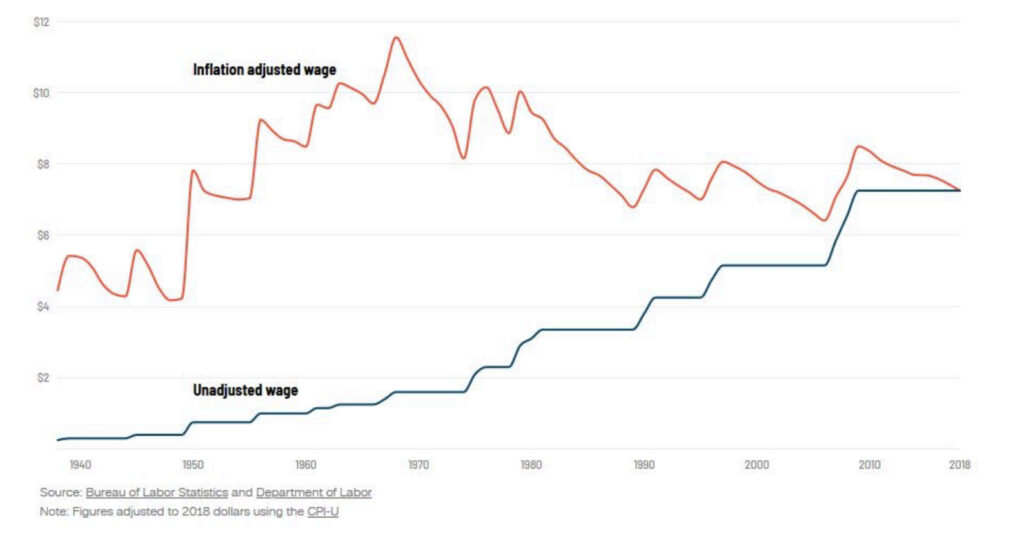

The federal minimum wage has not been increased in over eight years. If a person works minimum wage at $7.25 an hour, for 40 hours/week for 50 weeks/year, their annual salary is only $14,500. The national poverty threshold is at $13,064, and the U.S. government calculates the poverty line as an income three times the cost of a nutritionally adequate diet. What this goes to show is that a person working minimum wage, without considering other factors such as geographic location, is just barely scraping by. This is extremely concerning as the stagnation of wages in conjunction with the ever-rising cost of living will trap more Americans living in poverty

Unfortunately, poverty lines and other government poverty statistics do not accurately portray the real economic disparities Americans face today. This is because many of these government statistics fail to take shelter, transportation, medical care, and childcare costs into account. Poverty statistics oftentimes also fail to account for geographical differences, as living costs in California are drastically different than those in Mississippi. A recent poll conducted by the Center for American Progress poll found that “43% of people cannot afford to pay for necessities, 40% would struggle to find $400 in an emergency.” Millions of Americans are struggling just to get food on the table. What this data suggests is that there are far more people living the realities of poverty than what the poverty line suggests. An effective way to combat the rising costs of living and address the issues of poverty is to increase the minimum wage. According to Taylor, “The U.S. Department of Labor reviewed 64 studies on the effects of minimum wage increases and unemployment and found no correlation between the two. A groundbreaking study … for Research on Labor and Employment demonstrated that a $15 minimum wage would not create job loss but would lift more people out of poverty.” What this shows is that raising the minimum wage would not only help people with lower incomes achieve a better standard of living but reduce a major stressor that is detrimental to health and well-being.

In essence, poverty has many adverse effects and is directly related to diet and health issues. During my six years as a volunteer at the local food shelter, I saw first-hand the detriment of poverty and its effects on the local community. Despite the United States being one of the wealthiest countries in terms of resources and GDP, the significant income inequality gap has made the U.S. ranked fourth in highest poverty rate. As a result, because of a person’s socioeconomic status, a person’s health and wellness can vastly differ based on their income. The leading cause of death in the United States are chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease-all exacerbated by the ever-rising amount of people experiencing poverty and food choices of those in lower-income. With the ever-rising costs in housing, education, necessities, and the stagnation of wages, it has become harder to achieve a comfortable standard of living and escape the cycle of poverty.

References

Alain, A. (2019, May 27). Nearly 40% of Americans can’t cover a surprise $400 expense. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/nearly-40-of-americans-cant-cover-a-surprise-400-expense/

Daniel Taylor, T. P. I. (2019, October 26). Opinion: I’m a Philadelphia pediatrician. Here’s the one thing that would help my patients most. WHYY. https://whyy.org/articles/im-a-philadelphiapediatrician-heres-the-one-thing-that-would-help-my-patients-most/

Darmon, Nicole, Adam Drewnowski. “Does Social Class Predict Diet Quality?” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 87(5) May 2008: pp.1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107

Donkin, A. J. M. (2014, February 21). Social gradient. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118410868.wbehibs530

Galea, S. (2019). Well: What we need to talk about when we talk about health. Oxford University Press.

Rhone, A. (2021, May 24). Documentation. USDA ERS – Documentation. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation/

Simon, K. M., Manseau, M. W., & Beder, M. (2018, June 29). Addressing poverty and mental illness. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/addressing-poverty-andmental-illness

Smith, C., & Morton, L. W. (2009). “Rural food deserts: low-income perspectives on food access in Minnesota and Iowa.” Journal of nutrition education and behavior, 41(3), pp.176–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.06.008

Vornic, A. (2020, July 13). As more go hungry and Malnutrition persists, achieving ZERO hunger by 2030 in doubt, UN Report warns. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news/item/13-07-2020-as-more-go-hungry-and-malnutrition-persists-achieving-zero-hungerby-2030-in-doubt-un-report-warns

About the author

Tyler Huang

Tyler Huang is a senior at Brunswick High School in Brunswick, Georgia. He is an active member of the local community and has deep passion for social activism, including building better access to healthy foods among low-income and marginalized communities.